recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;" width="630" height="110" />

recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;" width="630" height="110" />The greatest triumph of the Paris climate agreement is that there is an agreement at all.

Unlike previous attempted climate treaties, Paris encompasses not only an affluent United States, but also a transformed China and an industrializing India. It even bears the moral imprimatur of the Pacific Island states, countries existentially threatened by sea-level rise.

This global solidarity gives the Paris agreement its power. As I wrote over the weekend, the deal is a strange one. While it will affect policies domestic and international, it is meant to work more as an economic signal than as a binding statute. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry has said that it sends “a critical message to the global marketplace” to invest in green energy. This signal springs in great part from its unity.

But to reach concord on a single document, the 195 negotiating countries had to address six thorny issues that have long been central to international climate diplomacy. We previewed these last week: They’re often questions of historical responsibility and future ambition which have an additional technical or financial dimension.

The final deal finesses solutions to some of these problems and delays answers to others. But since much of the final adopted document exists to handle these questions with care, to revisit them is to get a guided tour of the agreement—a document which will now help decide human civilization’s fate.

How much should the world limit warming?

The problem: In 2009, the world’s nations agreed: The global temperature average should not be allowed to rise more than two degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels.

Since then, study after study has emphasized the dangers of a two-degree-warmed world and the simultaneous difficulty of actually halting climate change there. When Paris began, some observers expected the UN to abandon the two-degree limit in favor of something more realistic.

Instead, nations began endorsing a more ambitious path. More than 100 countries, including the United States, announced their support for limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Many island nations declared they could not accept anything more. Even China signaled its endorsement.

The solution: The final Paris agreement retains the two-degree target, while recognizing the importance of pursuing 1.5 degrees. Article 2, Section 1 deals most directly with temperature limits:

recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;" width="630" height="110" />

recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;" width="630" height="110" />

Including the 1.5 degree target is a triumph for both green activists and the most climate-vulnerable nations. But Rachel Cleetus, the lead economist and climate-policy manager at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said that the phrase “well below 2 degrees Celsius” was also noteworthy. It’s “the first time we’ve ever seen this kind of language in a global context,” she told me.

The agreement also directed the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—the climate-science arm of the UN—to draw up a report by 2018 on how to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius.

How quickly will the world abandon fossil fuels?

The problem: If humanity hopes to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100, it must essentially stop emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere by 2060, according to a recent study from Nature Climate Change. (Then it must start pulling carbon out of the atmosphere—no easy feat.)

But would the Paris agreement come out and say that? Delegates could not agree. Small island states wanted forceful language, calling for draft phrases like “zero global [greenhouse-gas] emissions by 2060” or “decarbonization as soon as possible after mid-century.” But Saudi Arabia said that such a goal was a “threat to sustainable development”— which some interpreted as meaning a threat to its oil production. And according to The New York Times, petroleum-pumping Venezuela was also skeptical of long-term decarbonization language.

The solution: The final version of the Paris text, Article 4, Section 1, resolves to peak global greenhouse-gas emissions as soon as possible. Then, after 2050, it says that all anthropogenic emissions should be balanced with “removal by sinks”:

best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty." width="630" height="101" />

best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty." width="630" height="101" />

“That’s essentially a net-zero goal,” said Cleetus. She hailed the wording, saying it is “the language we need to deliver on this type of an ambition.”

Some have noted the technological ambiguity in this article. Forests and oceans can both serve as carbon “sinks”—that is, both absorb carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. But one day, humanity might be able to deploy negative-emissions technologies at scale, which could absorb and thus “neutralize” any additional carbon emissions. Indeed, the European Union’s climate chief said after the conference that the 1.5-degree target will require use of such tech.

While the article doesn’t rule out carbon scrubbers, Cleetus pointed out that Article 5, Section 1 explicitly calls out forests as the kind of “sinks” being discussed:

Who should pay for the costs of climate change, and how much should they give?

The problem: Surprise, surprise: “Climate finance”—that is, who gets money, and who gives it—was one of the most controversial issue at the Paris talks.

In order to salvage the 2009 climate talks in Copenhagen, Hillary Clinton, then the U.S. secretary of state, pledged that the rich world would “mobilize” $100 billion to help developing countries make their economies more sustainable and prepare for the storms to come. The key word was mobilize: Unlike traditional foreign aid, where government money is redirected to poorer countries or aid organizations working there, the U.S. and the EU would arrange for billions to flow from a variety of sources, public and private.

Would that count? And would the rich world be defined strictly as the U.S., the EU, Canada, and Japan? The United States preferred for China and India—two wealthy, powerful nations that also contain hundreds of millions of people still in poverty—to pitch into that $100 billion target. Yet even as those two Asian nations talked up their own investment in climate-vulnerable nations, they blanched at being compelled to join the rich world’s pledge.

The solution: So here’s something counter-intuitive. The text commonly called the “Paris Agreement” is actually two different documents: the agreement itself, which is legally binding, and the Paris decision, which passes the agreement and sets out a number of less legally binding ways to approach and observe it.

The Paris agreement includes no new specific commitments to finance. But item 115 of the Paris decision says that more than that $100 billion will be needed:

How often should nations check and reassess their emission reductions?

The problem: Two different mechanisms apply here.

The first is stock-taking, when countries will announce how they’ve reduced carbon emissions. The draft Paris agreement now says global stock-takes will take place every five years. It also says that the first stocktake will happen in either 2023 or 2024, though the United States wants them to start earlier. The New York Times reports that the U.S. is angling for the first stock-take to come in 2019 or 2021—both non-presidential election years.

The second is ratcheting, when countries will announce more ambitious emissions reductions. India hopes for ratchet sessions to come every 10 years, saying its short-term goal must be lifting its people out of poverty. The U.S. and the Pacific Island nations wants countries to ratchet every five years.

The solution: Article 14 of the Paris agreement deals with both stocktaking and ratcheting. It announces that the first stocktake will occur in 2023, then every five years, and that countries should “update and enhance” individual plans at that and future meetings.

best available science. 2. The Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement shall undertake its first global stocktake in 2023 and every five years thereafter unless otherwise decided by the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement. 3. The outcome of the global stocktake shall inform Parties in updating and enhancing, in a nationally determined manner, their actions and support in accordance with the relevant provisions of this Agreement, as well as in enhancing international cooperation for climate action." width="630" height="206" />

best available science. 2. The Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement shall undertake its first global stocktake in 2023 and every five years thereafter unless otherwise decided by the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement. 3. The outcome of the global stocktake shall inform Parties in updating and enhancing, in a nationally determined manner, their actions and support in accordance with the relevant provisions of this Agreement, as well as in enhancing international cooperation for climate action." width="630" height="206" />

And item 20 of the Paris decision says that a “facilitative dialogue”—don’t call it a stocktake—will take place in 2018. Nations are expected to improve their plans at that meeting, too:

Who should make sure nations meet their reduction goals?

The problem: The United States wanted an outside agency, perhaps similar to the International Atomic Energy Agency, to make sure nations keep the promises they made before the Paris talks to cut emissions. China, India, and other developing countries said they were skeptical of third-party oversight.

The solution: No outside agency will approve and oversee whether nations are keeping their words—this was a red line for China and India, according to Cleetus. But under Article 13, nations will be subject to a common framework of transparency, though it will recognize that developing countries may need more help reaching their goal. Here’s a taste of the language of that article, from sections 11 and 12:

best available science. 2. The Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement shall undertake its first global stocktake in 2023 and every five years thereafter unless otherwise decided by the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement. 3. The outcome of the global stocktake shall inform Parties in updating and enhancing, in a nationally determined manner, their actions and support in accordance with the relevant provisions of this Agreement, as well as in enhancing international cooperation for climate action. " width="630" height="171" />

best available science. 2. The Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement shall undertake its first global stocktake in 2023 and every five years thereafter unless otherwise decided by the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement. 3. The outcome of the global stocktake shall inform Parties in updating and enhancing, in a nationally determined manner, their actions and support in accordance with the relevant provisions of this Agreement, as well as in enhancing international cooperation for climate action. " width="630" height="171" />

Who is responsible for the loss and damage caused by climate change?

The problem: As climate change worsens, it will assault not only coastal cities and settlements, but also rural farmers and fishers who depend on predictable seasons and reliable ocean currents. Who should pay for all the infrastructure deluged and harvests lost? In 2013, a UN climate conference began establishing an international loss-and-damage mechanism to address these concerns.

The United States and other developed countries—which, after all, have emitted most of the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere right now and thus are responsible for that warming—say they want to help. But they cannot abide what would amount to climate reparations. “The U.S. clearly acknowledges that these impacts are being felt, but it does have a red line around increases of compensation and liability,” says Cleetus.

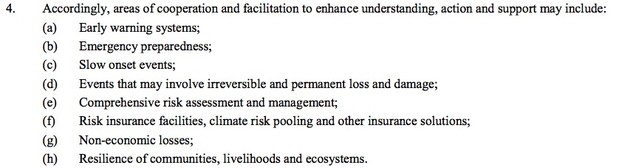

The solution: A standalone section of the Paris agreement, Article 8, addresses loss and damage, as climate-vulnerable countries wanted. This section lists ways that developed countries could assist climate-threatened developing countries:

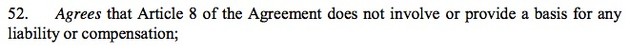

And item 52 in the Paris decision lets developed countries recognize the importance of funding for loss and damage without being liable for climate reparations. Cleetus said it was drafted specifically to allay U.S. concerns about “liability or compensation”:

Who bears responsibility for protecting the climate, anyway?

The problem: In 1992, the world adopted the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This document has guided all future climate diplomacy: This climate convention in Paris formally meets under its auspices. The framework convention establishes the principle of “c ommon but differentiated responsibility” for protecting the climate system: That is, everyone has a role to play in keeping the world safe, but highly developed countries have the most responsibility. (This important phrase also gave rise to the best initialism ever.)

Now, many developed countries want to make sure this principle is adhered to: the differentiated as much as the common. There’s no single blurb of text to point to that demonstrates this principle, Cleetus told me during the talks, but developing countries want it to be a common thread through the text.

“Mitigation commitments, finance commitments—developing countries were asking for these issues to be seen together,” she said. They needed “to be decided together under the convention rather than as one-off agreements on specific pieces of it.”

The solution: For two decades, international climate diplomacy has clung to a bifurcated model of how the world works. There are developed countries (“Annex 1 countries,” in the lingo) and developing countries (“non-Annex 1 countries”), and—so the story went—developed countries would decarbonize much faster than developing countries could.

The Paris agreement abandons this separation, but, said Cleetus, it preserves a sense of “common but differentiated responsibility.” The transparency language provides a good example of this: All nations exist under the same transparent reporting scheme, but there’s a differentiation in how that transparency will occur.

This better aligns with how climate action must happen and how it is happening, said Cleetus. “China is taking on cap-and-trade before the U.S. has taken it on as a nation,” she told me. India is planning to roll out 100 gigawatts of solar energy, an amount that will dwarf that in the States.

“Everyone is doing the best they can in spite of their national circumstances,” Cleetus said. And to her mind, that includes the United States, which is debuting its climate-change policies not as legislation but as executive actions targeted at the power sector.

“We have a Congress that’s really not demonstrating leadership on this issue,” she said, an oblique reference to the fact that more than half of Congressional Republicans doubt the reality of climate change. “Congress needs to step in and take greater leadership on this,” she said. Otherwise, the nations we used to call “developing” will.